|

The Civil Rights movement made its fight against segregation in Birmingham a model of direct action that inspired other cities, attracted immense media attention, and helped bring about the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

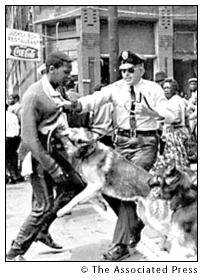

Ethel Payne came to the city in May to cover the controversial Children’s Crusade in which thousands of students left school and marched. Over several days hundreds of students were arrested, dispersed with powerful water hoses, and even attacked by the notorious dogs under the control of Public Safety Commissioner Eugene “Bull” Connor.

Payne and other reporters stayed at the A.G. Gaston Motel, where Martin Luther King and other movement leaders camped when in town.

One night, confined to their rooms by a heavy downpour, the reporters heard a loud knock. Opening the door they found New York Post reporter Murray Kempton dripping wet with a bulky package tucked under his raincoat

“You all can’t have any of this,” Kempton exclaimed to the black reporters in the room, “this is white folks’ whiskey.”

Kempton's sarcastic remark was prompted by his discovery that segregation was so rigid in Birmingham that the liquor store where he bought his whiskey had a barrier running down the store.

“There were certain brands of liquor on the one side for the whites and certain brands on the other side,” recalled Payne. But, in recounting this incident many years later, she added with a laugh, “The cash register was in the middle and it didn’t discriminate.”